Jay Doubleyou: rote learning

Pisa 2012 results: which country does best at reading, maths and science? | News | theguardian.com

Many in the West saw it as a 'wake-up' call:

OECD education report: subject results in full - Telegraph

German teens perform 'lower than expected' on global PISA skills test | News | DW.DE | 01.04.2014

But here's a very different view on how West and East compare:

Be Glad for Our Failure to Catch Up with China in Education

Our schools are better than China’s because ours don’t work as well as theirs.

Published on May 28, 2013 by Peter Gray in Freedom to Learn

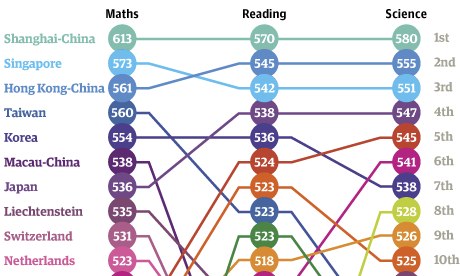

For more than 20 years we’ve had national educational goals aimed at emulating the Chinese (and Japanese and Korean) educational system. We’ve been working toward more centralization of control, more standardization of curricula and methods, and more student time in the classroom and at homework, all in an effort to produce higher scores on standardized tests. This was embodied in Clinton’s “Goals 2000” in the 1990’s, Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” in the next decade, and now Obama’s “Race to the Top.” We’re embarrassed every time international tests show our schoolchildren scoring low compared to those in other countries. When Shanghai’s 15-year-olds topped the charts in reading, math, and science on the 2010 PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) exam and we were far behind, our educational leaders once again affirmed the commitment to emulate the Chinese. Education Secretary Arne Duncan called it a “wakeup call.”[1, p 120]

For more than 20 years we’ve had national educational goals aimed at emulating the Chinese (and Japanese and Korean) educational system. We’ve been working toward more centralization of control, more standardization of curricula and methods, and more student time in the classroom and at homework, all in an effort to produce higher scores on standardized tests. This was embodied in Clinton’s “Goals 2000” in the 1990’s, Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” in the next decade, and now Obama’s “Race to the Top.” We’re embarrassed every time international tests show our schoolchildren scoring low compared to those in other countries. When Shanghai’s 15-year-olds topped the charts in reading, math, and science on the 2010 PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) exam and we were far behind, our educational leaders once again affirmed the commitment to emulate the Chinese. Education Secretary Arne Duncan called it a “wakeup call.”[1, p 120]

You might think the Chinese educational leaders would be happy that their kids are scoring so high on these international competitions. But they’re not. More and more they realize that their system is failing terribly. At the same time that we are continuing to try to be more like them, they are trying—though without much success so far—to be more like us, or like we were before we began trying so hard to be like them. They see that their system is quashing creativity and initiative, with the result that it produces decent bureaucrats and number crunchers, but very few inventors and entrepreneurs. In response to the same PISA report that led Duncan to his “wakeup call,” Jiang Xuaqin, director of the International Division of Peking University High School, wrote this in the Wall Street Journal: “The failings of a rote-memorization system are well-known: Lack of social and practical skills, absence of self-discipline and imagination, loss of curiosity and passion for learning. … One way we will know when we’re succeeding in changing our schools is when those PISA scores come down.” (Italics added) [2]

Let’s look a little closer at the Chinese educational system.

According to a study conducted by the Hangzhou Education Science Publishing House, Chinese students spend nearly 10 hours per day studying in the primary grades, 11 hours per day in middle school, and 12.5 hours per day in high school.[3] Kieth Bradsher reported recently on the life of a typical Chinese high school student: “She woke up at 5:30 every morning to study, had breakfast at 7:30, then attended classes from 8:30 a.m. to 12:30; 1:30-5:30 in the afternoon; and 7:30-10:30 in the evening. She studied part of the day on Saturdays and Sundays.”[4] David Jiang, an American born Chinese who went to China for his high-school years, wrote in his blog: “What I saw around me [in high school] was a mass of zombies. … It is here that I realized how shallow grades were….”[5]

Chinese students do all this study for one and only one reason—to get a high score on the gaokao, the national examination that is the sole criterion for admitting students to college. Every parent, every teacher, is in competition with other parents and teachers to wring the highest scores they possibly can out of their children. Many parents punish their children physically for failure in school, and any performance not at or near the top is considered failure.

A recent large-scale survey of children in Chinese primary schools, conducted by Chinese and British researchers, revealed massive psychological suffering. The authors summarized the results as follows: “Eighty-one per cent worry 'a lot' about exams, 63% are afraid of the punishment of teachers, 44% had been physically bullied at least sometimes, with boys more often victims of bullying, and 73% of children are physically punished by parents. Over one-third of children reported psychosomatic symptoms at least once per week, 37% headache and 36% abdominal pain. All individual stressors were highly significantly associated with psychosomatic symptoms. Children identified as highly stressed (in the highest quartile of the stress score) were four times as likely to have psychosomatic symptoms.” [6]

The highest scorers on the gaokao each year are celebrated in the Chinese press; they and their parents become temporarily famous. But follow-up studies reveal that test scores don’t predict future success. The high scorers do not achieve beyond their lower-scoring peers once they leave school; in fact, the results of one study suggested that the highest scorers achieved less, on average, than those who scored lower.[7, p 82] Indeed, according to Yong Zhao, an expert on Chinese education, a common term used in China now to refer to the general results of their educational system is gaofen dineng, which means, literally, high scores but low ability. Because students spend nearly all of their time studying, they have little chance to do anything else. They have little opportunity to be creative, take initiative, or develop physical and social skills.

Yong Zhao grew up in China, so he experienced the Chinese educational system first hand. He is now a professor of education at the University of Oregon, has two children in American schools, and has focused much of his research on the similarities and differences between Chinese and American schooling and their economic consequences. In two recent books-- Catching up or Leading the Way (2009) and World Class Learners (2012)—he describes the harm of China’s educational system and documents their interest in reforming it.

In addressing the question of why the US system has produced better real-world results than the Chinese system, Zhao writes, “The short answer is that American education has not been as good as the Chinese at killing creativity and the entrepreneurial spirit. In the most fundamental ways, American education operates under the same paradigm as the Chinese. … In a nutshell, both American education and Chinese education are designed to turn a group of children into products with similar specifications indicated by how much they have mastered the curriculum, that is, what the adult decides they should know and be able to do, regardless of their backgrounds, interests, and differences.” [1, p 134-135]

Zhao goes on to explain that the advantage of the American system is that it fails to do very well what it wants to do; it fails to bring American kids into line. His analogy is that the American system is like a sausage machine that isn’t very good at making sausages, so sometimes it spits out things quite unlike sausages.

Leaders in China want to emulate the American educational system, and leaders in America want to emulate the Chinese system. Maybe in a few years, if the leaders get their way, the Chinese will be doing all the inventing and we’ll be keeping our pediatricians and child psychiatrists even busier than they already are with stress-induced childhoodillnesses.

I say, let’s do away entirely with our system of top-down, forced education. Let’s scrap the sausage machine and, instead, provide the conditions that will allow all children to educate themselves freely, in their own chosen ways, without having to fight the school system to do it. For more on that, see Free to Learn.

-----------

What do you think? Do you have any experience with Chinese or other East Asian schools? This blog is a forum for discussion, and your stories, comments, and questions are valued and treated with respect by me and other readers. As always, I prefer if you post your comments and questions here rather than send them to me by private email. By putting them here, you share with other readers, not just with me. I read all comments and try to respond to all serious questions, if I feel I have something useful to say. Of course, if you have something to say that truly applies only to you and me, then send me an email.

-----------

References

[1] Yong Zhao (2012), World class learners: Educating creative and entrepreneurial Students.

[2] Jiang Xueqin. The Test Chinese Schools Fail: High Scores for Shanghai’s 15-year-olds are actually a sign of weakness. Wall Street Journal, December 8, 2010.

[3] See Zhao, 2012, pp 1240125.

[4] Kieth Bradsher. In China, Betting It All on a Child in College. New York Times, Feb. 16, 2013.

[5] David Jiang (July 12, 2011). China; Education System Made Me an Individual. http://diaspora.chinasmack.com/2011/usa/david-jiang-china-education-system-made-me-an-individual.html

[6] Hesketh T, Zhen Y, Lu L, Dong ZX, Jun YX, Xing ZW. Stress and psychosomatic symptoms in Chinese school children: cross-sectional survey. Arch Dis Child. 2010 Feb;95(2):136-40. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.171660. Epub 2010 Feb 4.

[7] Yong Zhao (2009), Catching up or leading the way: America education in the age of globalization.

Be Glad for Our Failure to Catch Up with China in Education | Psychology Today

.

.

.

Published on May 28, 2013 by Peter Gray in Freedom to Learn

For more than 20 years we’ve had national educational goals aimed at emulating the Chinese (and Japanese and Korean) educational system. We’ve been working toward more centralization of control, more standardization of curricula and methods, and more student time in the classroom and at homework, all in an effort to produce higher scores on standardized tests. This was embodied in Clinton’s “Goals 2000” in the 1990’s, Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” in the next decade, and now Obama’s “Race to the Top.” We’re embarrassed every time international tests show our schoolchildren scoring low compared to those in other countries. When Shanghai’s 15-year-olds topped the charts in reading, math, and science on the 2010 PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) exam and we were far behind, our educational leaders once again affirmed the commitment to emulate the Chinese. Education Secretary Arne Duncan called it a “wakeup call.”[1, p 120]

For more than 20 years we’ve had national educational goals aimed at emulating the Chinese (and Japanese and Korean) educational system. We’ve been working toward more centralization of control, more standardization of curricula and methods, and more student time in the classroom and at homework, all in an effort to produce higher scores on standardized tests. This was embodied in Clinton’s “Goals 2000” in the 1990’s, Bush’s “No Child Left Behind” in the next decade, and now Obama’s “Race to the Top.” We’re embarrassed every time international tests show our schoolchildren scoring low compared to those in other countries. When Shanghai’s 15-year-olds topped the charts in reading, math, and science on the 2010 PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) exam and we were far behind, our educational leaders once again affirmed the commitment to emulate the Chinese. Education Secretary Arne Duncan called it a “wakeup call.”[1, p 120]You might think the Chinese educational leaders would be happy that their kids are scoring so high on these international competitions. But they’re not. More and more they realize that their system is failing terribly. At the same time that we are continuing to try to be more like them, they are trying—though without much success so far—to be more like us, or like we were before we began trying so hard to be like them. They see that their system is quashing creativity and initiative, with the result that it produces decent bureaucrats and number crunchers, but very few inventors and entrepreneurs. In response to the same PISA report that led Duncan to his “wakeup call,” Jiang Xuaqin, director of the International Division of Peking University High School, wrote this in the Wall Street Journal: “The failings of a rote-memorization system are well-known: Lack of social and practical skills, absence of self-discipline and imagination, loss of curiosity and passion for learning. … One way we will know when we’re succeeding in changing our schools is when those PISA scores come down.” (Italics added) [2]

Let’s look a little closer at the Chinese educational system.

According to a study conducted by the Hangzhou Education Science Publishing House, Chinese students spend nearly 10 hours per day studying in the primary grades, 11 hours per day in middle school, and 12.5 hours per day in high school.[3] Kieth Bradsher reported recently on the life of a typical Chinese high school student: “She woke up at 5:30 every morning to study, had breakfast at 7:30, then attended classes from 8:30 a.m. to 12:30; 1:30-5:30 in the afternoon; and 7:30-10:30 in the evening. She studied part of the day on Saturdays and Sundays.”[4] David Jiang, an American born Chinese who went to China for his high-school years, wrote in his blog: “What I saw around me [in high school] was a mass of zombies. … It is here that I realized how shallow grades were….”[5]

Chinese students do all this study for one and only one reason—to get a high score on the gaokao, the national examination that is the sole criterion for admitting students to college. Every parent, every teacher, is in competition with other parents and teachers to wring the highest scores they possibly can out of their children. Many parents punish their children physically for failure in school, and any performance not at or near the top is considered failure.

A recent large-scale survey of children in Chinese primary schools, conducted by Chinese and British researchers, revealed massive psychological suffering. The authors summarized the results as follows: “Eighty-one per cent worry 'a lot' about exams, 63% are afraid of the punishment of teachers, 44% had been physically bullied at least sometimes, with boys more often victims of bullying, and 73% of children are physically punished by parents. Over one-third of children reported psychosomatic symptoms at least once per week, 37% headache and 36% abdominal pain. All individual stressors were highly significantly associated with psychosomatic symptoms. Children identified as highly stressed (in the highest quartile of the stress score) were four times as likely to have psychosomatic symptoms.” [6]

The highest scorers on the gaokao each year are celebrated in the Chinese press; they and their parents become temporarily famous. But follow-up studies reveal that test scores don’t predict future success. The high scorers do not achieve beyond their lower-scoring peers once they leave school; in fact, the results of one study suggested that the highest scorers achieved less, on average, than those who scored lower.[7, p 82] Indeed, according to Yong Zhao, an expert on Chinese education, a common term used in China now to refer to the general results of their educational system is gaofen dineng, which means, literally, high scores but low ability. Because students spend nearly all of their time studying, they have little chance to do anything else. They have little opportunity to be creative, take initiative, or develop physical and social skills.

Yong Zhao grew up in China, so he experienced the Chinese educational system first hand. He is now a professor of education at the University of Oregon, has two children in American schools, and has focused much of his research on the similarities and differences between Chinese and American schooling and their economic consequences. In two recent books-- Catching up or Leading the Way (2009) and World Class Learners (2012)—he describes the harm of China’s educational system and documents their interest in reforming it.

In addressing the question of why the US system has produced better real-world results than the Chinese system, Zhao writes, “The short answer is that American education has not been as good as the Chinese at killing creativity and the entrepreneurial spirit. In the most fundamental ways, American education operates under the same paradigm as the Chinese. … In a nutshell, both American education and Chinese education are designed to turn a group of children into products with similar specifications indicated by how much they have mastered the curriculum, that is, what the adult decides they should know and be able to do, regardless of their backgrounds, interests, and differences.” [1, p 134-135]

Zhao goes on to explain that the advantage of the American system is that it fails to do very well what it wants to do; it fails to bring American kids into line. His analogy is that the American system is like a sausage machine that isn’t very good at making sausages, so sometimes it spits out things quite unlike sausages.

Leaders in China want to emulate the American educational system, and leaders in America want to emulate the Chinese system. Maybe in a few years, if the leaders get their way, the Chinese will be doing all the inventing and we’ll be keeping our pediatricians and child psychiatrists even busier than they already are with stress-induced childhoodillnesses.

I say, let’s do away entirely with our system of top-down, forced education. Let’s scrap the sausage machine and, instead, provide the conditions that will allow all children to educate themselves freely, in their own chosen ways, without having to fight the school system to do it. For more on that, see Free to Learn.

-----------

What do you think? Do you have any experience with Chinese or other East Asian schools? This blog is a forum for discussion, and your stories, comments, and questions are valued and treated with respect by me and other readers. As always, I prefer if you post your comments and questions here rather than send them to me by private email. By putting them here, you share with other readers, not just with me. I read all comments and try to respond to all serious questions, if I feel I have something useful to say. Of course, if you have something to say that truly applies only to you and me, then send me an email.

-----------

References

[1] Yong Zhao (2012), World class learners: Educating creative and entrepreneurial Students.

[2] Jiang Xueqin. The Test Chinese Schools Fail: High Scores for Shanghai’s 15-year-olds are actually a sign of weakness. Wall Street Journal, December 8, 2010.

[3] See Zhao, 2012, pp 1240125.

[4] Kieth Bradsher. In China, Betting It All on a Child in College. New York Times, Feb. 16, 2013.

[5] David Jiang (July 12, 2011). China; Education System Made Me an Individual. http://diaspora.chinasmack.com/2011/usa/david-jiang-china-education-system-made-me-an-individual.html

[6] Hesketh T, Zhen Y, Lu L, Dong ZX, Jun YX, Xing ZW. Stress and psychosomatic symptoms in Chinese school children: cross-sectional survey. Arch Dis Child. 2010 Feb;95(2):136-40. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.171660. Epub 2010 Feb 4.

[7] Yong Zhao (2009), Catching up or leading the way: America education in the age of globalization.

Be Glad for Our Failure to Catch Up with China in Education | Psychology Today

.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment